Sallust

Gaius Sallustius Crispus (86/85 BC-35 BC?, anglicized as “Sallust”), 85BC - 35BC?, was a Roman politician during the era shortly before and after the civil war that saw Caesar's rise to power and marked the end of the Roman Republic, known to be the earliest attested Roman historian to write integrally in Latin, of which two major works are known: his accounts on both the Catilinarian Conspiracy (63 BC) and on the war against Numidia and its king Jugurtha (112-106BC).

Most of the stuff you can read about Sallust, and his intent to underline the moral decline he perceived to be running rampant by the end of the Republic Era, are readily available at Wikipedia as per usual; in here, however, I'm at liberty to add some extra info and minutiae about both author and work.

Biography

Born during one of the most pivotal moments in Rome's existence and witness to the civil war that installed Julius Caesar as ruler of Rome, it's nothing short of miraculous that Sallust is so succinctly attested historiographically: a passage in Bellum Africanum1) mentions him by his full name, gracefully tying the knot of historical accuracy. In a time so tumultous for the Roman state, where the plebeians have slowly upturned the perpetual class struggle of the Republic to their favor by securing political privileges for themselves (such as participation in the cursus honorum2)), it comes as no wonder that his writings reflect equally political overtones, i.e. overtones chock full of moralism. This is probably also compounded with the fact that he was born in Sabine country, traditionally known for their rigid adhesion to customs and tradition3).

Sallust, like most Roman historians, was involved in military and political affairs - the most a Roman citizen could aspire to. This comes as no surprise as these men were heavily instructed in the art of writing, oratory and rhetoric. A good chunk of Roman historiography comes in fact from politicians or servicemen who participated from history as actors first and memoir author second (either of events they participated in or of those they didn't), which also explains the moralist tint peppered in their texts: after all, people who look approvingly of a certain event (let alone those who participated in it) will likely attempt to justify it, saving face for themselves in the process. Sallust climbed the Roman status ladder in a time where the decay of Republican institutions could no longer be ignored: the galvanization of class struggle between Optimates and Populares4) into the first Civil War, the slave rebellion of Spartacus (that came so close to the Republican nerve center that confidence in Roman military took a nosedive), the conflict against Cilician pirates, and eventually the coup attempt by Catiline and his co-conspirators. By the time Sallust became quaestor (not an easy task for a man without family connections regardless of his wealth, it's assumed that he lapped up to Pompey Magnus to ease his way in), Rome was only six years away from all-out war between Caesar and the Senate. In three years, Sallust becomes a tribune for the plebeians right as popular former plebeian tribune Publius Clodius is slain by a gang under the command of Patrician supporter Titus Milo after a year of gang wars in the streets of Rome5), and after a process of almost-unprecedented acephaly Pompey Magnus was chosen as sole consul, which in turn lead to the persecution of Clodian supporters.

Sallust escaped trial and was never tried for his explicit support of Clodius, most likely due to his friendship with Pompey6). He even makes peace with Cicero and Titus Milo himself, a move transparently seen as opportunistic by modern commentators and perhaps even by contemporaries of Sallust, as he defends himself in one of his works saying that old age was conducive for his soul to become corrupted by ambition7). Some believe that he became proquaestor of Syria shortly after, although by that time he was more than eligible for a senatorial position; while it makes no sense for him to have taken a title so below his stature, it is indeed stated that Sallust was expelled from the Senate either because of his affiliations to Clodius (in which his expulsion is taken as a “this is as far you go” sign) or because of rumors of personal debauchery that peaked with Sallust being caught banging Sila's daughter. Sallust joins Caesar's side roughly around the same time the latter famously crosses the Rubicon and is eventually chosen as Praetor for the province of Africa Nova (part of modern-day Algeria, Tunisia, etc) and proceeds to pillage and squander the riches this territory offered. Accused under the lex Iulia de repetundis8), he walks away scot free (no doubt by Caesar himself ordering that the trial does not proceed) and uses the money to build a palatial garden (the so-called Horti Sallustiani, the Sallustian Gardens)9) which was eventually annexed as part of the Imperial building complex.

All known accounts of Sallust's life, or at least those of him as a political figure, end around here. He spent roughly ten years in retirement in which it's believed his work was written: The Catilinarian Conspiracy c. 42-41 BC, The Jugurthine War c. 40BC, and up to his death in c. 35 BC (a time by which the Roman civil war, with Caesar now dead, was now focused in the brawl between Octavian and Mark Anthony), his Histories of which only fragments survive. It's believed that, given his inclination towards a more artistic, rhetoric-laden prose that not only narrates historical events but frames them within predications of virtues and vices, Sallust is the first and foremost Roman historiographer, following the style paradigms settled first by his Greek predecessors.

Catiline

Catiline is the shorthand name (in Italics from hereon) for Sallust's monograph on the so-called Catilinarian Conspiracy, which has received different related titles according to whoever copied the manuscript at that time: The Catilinarian Conspiracy, The Catilinarian War (or “The Conspiracy/War of Catiline, and so forth), etc. It refers to the attempt by Roman patrician and senator Lucius Sergius Catilina to overthrow the government of the Roman Republic, at the time led by Cicero and Gaius Hybrida, through a combination of subterfuge within Roman walls and a heated recruitment of rival tribes and disaffected veterans of former dictator Sulla's camp. Catiline is clasically divided in chapters which, unlike more modern work, bear little influence to the flow of the narration and is mostly used for the sake of reference.

The first thirteen chapters of Catiline are usually deemed to be the work's introduction, with a sort of author's prologue within the first four. Once again, unlike the books one would be more used to, Sallust is unclear almost on purpose, making little reference to the work itself and being rather vague to the concepts and ideas of virtue he tries to bring forward in this prologue. It's generally accepted that tone of this prologue is mostly one of self-justification for Sallust, in which he (poorly, even) regurgitates Platonic concepts. If virtue comes from our actions, and what separates our actions from that of animals is the fact that our strength comes from our spirit, it is imperative for men to seek glory through smarts rather than through force - “for the glory of riches and beauty is weak and pliable, [while] we hold virtue lustrous, eternal”10). A question surfaces: are military actions the product of physical might or through the virtues of the soul? Sallust says both are required, as before one begins one must think, and once the thinking is done one must act immediately; but a brief historical summary of the actions of Cyrus and Athenians confirm that it's intelligence that prevails in warfare. He proceeds to double down saying that life without culture, even when the physical is a mandatory requirement (“All that men have ever achieved was throught tilling, navigating, building…”), is equal to death itself; it is better, he argues, to do good for the sake of the Republic and be a good orator… and this is where his justification for his work comes in. The rest of this prologue is about how Sallust undergoes the difficult task of writing about the glory of others and how he, as a young man, fell in the vices of greed and bribery during his early beginnings in politics as his “old age” failed him, while his spirit vehemently rejected such conduct. Sallust, now retired from politics, decides to expiate himself by taking his retirement not in idleness, but making himself useful by writing “unbiased” history of Rome (”…mostly because my mood was free of hopes, fears, or political partisanship.“).

A short biography of Catiline follows: Lucius Catiline, a patrician of noble lineage, was an individual of high spiritual and physical fiber yet holder of a perverse, psychopathic mindset. An avid enjoyer of death, looting and all-around destruction, during the consulship of Pompey Strabo11), yet another equally perverse character, he returned from Africa in 66 after a stint as Governor during which an endless list of atrocities were pinned to his name. It's implied that Lucius Sulla's dictatorship gave him a thirst for blood, as his family sank further in bankruptcy. The biography veers off as Sallust begins with a whole section about Roman history in Chapter 6, from the Trojan foundation under Aeneas up to the annihilation of Carthage; the purpose of his discousre to underline how the populace of Rome went from being a culturally heterogeneous, “vagabond” peoples to homogeneous concord in an organized society: this period of well-being and opulence, however, brings about envy from other nations to the point that, “for kings, the good are more suspicious than the bad, and others' merit for them was always terrible”. The youth became more martial, more willing to reach glory, “everybody hurrying to be the first to hit an enemy, to climb a wall, to be witnessed as he accomplishes the feat…”, and so society reaches balance between peace and war, where the least amount of strife for citizens is found. Rome began to build up greed between its citizens with the destruction of Carthage, which kickstarted a chain of generations of dispossessed soldiers for whom idleness and riches were “a calamity” and culminating in the germination of a wish for power. This, Sallust argues, is where Rome begins its decadence as “the inept”, i.e. those who don't know their place begin to beseech positions of power12).

Thus, it is in this degenerate state of the city in which Catiline finds likeminded people to become their minions for the cause: gamblers, gluttons, rapists, those who had nothing to lose and those who had everything to lose, Catiline offered them what they wanted in exchange for loyalty: money, food, prostitutes, and so on. Catiline was no saint either: the accusations go from banging a noblewoman to banging a Vestal Virgin, and also including the one time he killed a man because Catiline was banging his mom (A consul's daughter, no less). Sallust straight up describes him as utterly deranged, possessed almost. He taught the youth how to become more efficient criminals and once the situation was ripe for this urban proletariat that were still owed the spoils and debts from their time with Sulla, he began his assault against the Roman state right during a moment in which the Italian territories were military underpowered: the Senate as a whole was focused on Pompey Magnus' offensive against the East. He successfully convinced a number of senators and noblemen, particularly those that knew him from 66 BC, in which Catiline had previously conspired against the Senate by attempting to force his way in, probably to nullify the massive de repetundis trial against him for his pillaging of Africa. During his description of his first trial, Sallust trips balls a little bit and starts talking about some nobleman called Gnaeus Piso and an arrangement between him and Catiline that makes no historical sense. It feels like Sallust either based this one on hearsay or totally made him up himself.

A Catiline speech follows after in Chapter 20, which essentially consisted of reminding his co-conspirators that it was a battle for their freedom, as compliance with their republic has so far been rewarded with misery. For how long will they continue to endure such affront from the Senate? I'll grant you all the power and riches you deserve if I take control of the Senate as consul, he says! I'll cancel all your debts, I'll proscribe the rich, you'll be magistrate, you'll be a priest, you'll be able to fuck up that guy's house and fuck his wife! With such irresistible offers, a whole bunch of cronies decide to follow Catiline's camp. There's even rumors of the guy sealing the pact between him and the accomplices of his declaration by drinking all from the same chalice full of human blood and wine. Catiline was the embodiment of caricaturesque evil, Sallust says.

A little addendum that's unfortunately too anachronistic for it to have actually taken place such as it's written (and is, perhaps, just Sallust going out of his way to portray Catiline as a truly bad guy): out of the rather large list of people that attended Sallust's formal call to arms, there's another goonish character with the name of Quintus Curius, who happened to be banging13) a girl called Fulvia, promising her riches through Catiline's plan. The girl, in revenge, began to spread the rumors of Catiline's conjuration. While the first part of the event did happen (that is to say, Quintus Curius grooming this poor girl), it took place well after the events of the Catilinarian Conspiracy.

Catiline fails the elections, and the consulship goes to Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida14). This got everybody understandably worried as they were beginning to suspect that their boss was not delivering; however, this didn't stop an enraged Catiline from massively deploying manpower and mobilizing large sums of money and credit, putting him at the ready to initiate war. Sallust adds here, in the middle of Chapter 24, that Catiline liked to have sex with other men (and sometimes with extremely indebted female prostitutes!); there's a weird segue on how this was useful to use prostitutes of all sorts to sublevate slaves, and one example of them called Sempronia, a married and well-cultured woman which held no respect for herself nor her wealth as she spent on everything and fucked everyone.

Meanwhile, all of this was set as Catiline attempted to win the vote for consulship the following year, but loses again to Cicero. It's becoming obvious that the consul must be taken out. He continued to order the mobilization of his troops all around Rome's surrounding regions, while on the inside Catiline continued 24/7 15) to establish what can be essentially called a terrorist cell inside Rome that was routinely starting fires, taking over key places of the city, stalking and threatening senators, and walking around Rome carrying weapons (a big no-no under Roman law). At some point he gets tired and begins to tell his guys to get ready for general mobilization as soon as Cicero is assasinated, and a plan to jump him in his house first thing in the morning. It is apparently Quintus Curius again who, realizing how real shit was getting, told Fulvia all about it who in turn snitched to Cicero. The people approaching Cicero's house were barred from entrance and the plan fell through.

Cicero doesn't have enough information to go on, neither on the extent of Catiline's infiltration of Rome nor his army waiting outside the city, so he exposes the situation to the Senate, who in turn suggested back to the Consul to start passing laws against this threat which essentially translated as “organize an army and commence to wage war”. An intercepted letter gives the Senate an idea of Catiline's external manpower, and the Senate responds accordingly by mobilizing legions. This gets the population rather worried, and “to top it all, women, whom they were instilled a type of fear, that of war, to which, given the power of the State, they were not used to, they would hit themselves, extend their supplicating hands to the sky, consoled their small children, wouldn't stop asking questions, would get scared with any type of rumor, […], and distrusted their own fortune and that of the fatherland.”16)

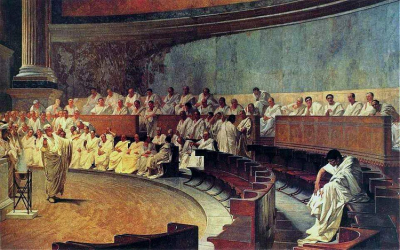

Catiline couldn't ignore the Senate's eye for much longer and presented himself to the senate, partly to play pretend and partly to have a chance to defend himself if someone were to call him out. It appears that when Cicero saw him he improvised a speech on the spot so masterful that Catiline was left speechless, only being able to beg the other senators not to listen to him.  Unable to defend himself, and being exposed to the entire Senate as an opportunist and a traitor to the patricial class, he left with the decision that preparations for all-out war were needed as the city was already well internally defended for more acts of arson and sabotage. He does, however, leave a few people behind to regroup the sleeper cell to be ready whenever Catiline strikes from outside. Catilina, meanwhile, writes letter to pretty much every ex-consul and influential nobleman he can remember, as he regroups his army outside Rome. Once the Senate found out Catiline was going to Manlius' main camp with the fasces and other official symbols of power, they're both deemed Public Enemies of the State of Rome, giving all their sympathizers a set date to lay down their arms without repercussions, otherwise capital punishment would be exacted upon everyone upon capture. Sallust makes a stop here to add that he personally remembers how much that period sucked, and what most people believed at the time: plebeians and poors, ready to be hopeful of anybody that offered them substantial change, were very much in favor of Catilina's plan, and many remembered how their victors became insanely rich after defeating Sulla. He observes that when Pompey Magnus goes to fight against Mithridates, the oligarchy began to show its influence on political affairs at the time; if Catiline had won the first battle, Sallust says, his people would've been unable to fill the power vacuum in time before the oligarchy striked back at the ready.

Unable to defend himself, and being exposed to the entire Senate as an opportunist and a traitor to the patricial class, he left with the decision that preparations for all-out war were needed as the city was already well internally defended for more acts of arson and sabotage. He does, however, leave a few people behind to regroup the sleeper cell to be ready whenever Catiline strikes from outside. Catilina, meanwhile, writes letter to pretty much every ex-consul and influential nobleman he can remember, as he regroups his army outside Rome. Once the Senate found out Catiline was going to Manlius' main camp with the fasces and other official symbols of power, they're both deemed Public Enemies of the State of Rome, giving all their sympathizers a set date to lay down their arms without repercussions, otherwise capital punishment would be exacted upon everyone upon capture. Sallust makes a stop here to add that he personally remembers how much that period sucked, and what most people believed at the time: plebeians and poors, ready to be hopeful of anybody that offered them substantial change, were very much in favor of Catilina's plan, and many remembered how their victors became insanely rich after defeating Sulla. He observes that when Pompey Magnus goes to fight against Mithridates, the oligarchy began to show its influence on political affairs at the time; if Catiline had won the first battle, Sallust says, his people would've been unable to fill the power vacuum in time before the oligarchy striked back at the ready.

One of Catiline's main men, Lentulus, was on the ground recruiting any parties that could be interested (with or without briberies involved) in joining the insurrection. Lentulus in turn indicates a guy named Publius Umbrenus to contact the Roman-annexed Gallic tribe of the Allobroges to recruit them for war; Umbrenus, well-known by various chieftains for having conducted business in Gaul before, intercepted the representatives of the Allobroges on the Forum to essentially convince them that their tribe had no way out of Roman-imposed debt, misery and death (as an annexed tribe, much of their production and wealth was siphoned towards the City as taxation and debt). Sallust also says the Allobroges really loved war so much so they should have cooperated… but for reasons unknown, the Allobroges ambassadors decide to snitch on them to a Cicero-affiliated nobleman. Cicero, once he had learned Catiline's final plan, asked the ambassadors to pretend to be interested to see just how much they could uncover from the inside.

Outside Rome, the operation was getting sloppy. Catiline has been logistically hyperactive to the point his movements looked like those of an alarmist rather than conniving coup attempt. Inside the City, however, Lentulus and others had raised a veritable army ready to strike from the inside and a cell of saboteurs which, when the signal was given, were meant to enact a very precise plan through an initial distraction by arson following with the assassination of Cicero and other key political figured, before regrouping with Catiline. The Allobroges contact Lentulus again… to ask for their plan to be put on paper to provide legitimacy once their ambassadors presented the case to the tribe alongside another henchman by the name of Titus Volturcius. Cicero gets a copy in the process and intercepts Volturcius by an ambush, thus nullifying the Allobroges relief force.

Cicero is now faced with the fact that, with danger over, came the time to think what possible punishment could apply to such important citizens, and the effect of their punishment on the population would be: The death penalty would burden the soul of all Romans (Or at least Cicero's), but impunity would only cause the Republic's ruin. The entire gang of conspirators inside the walls, including Lentulus, are called to testify to the Senate17). Volturcius' interrogation gave messy and contradictory results until protection was offered by the Senate, which causes him to snitch on the few co-conspirators he knew of. Once a handful of letters are publicly read (there's even one of them where Lentulus pretty much says the Oracles had destined him as the ruler of Rome), they're all arrested. Once the jig was up, the plebeians quickly saw the writing on the wall and began to renounce the idea of the coup and extol the virtues of Cicero himself instead, in a classic act of sucking up to the winner. Besides, when the plan about setting the city on fire caught on, nobody could in good faith justify Catiline's intentions as arson was particularly cruel, doubly so for plebeians with few material goods; arson as a tool for warfare was seen as a particularly heinous war crime18).

More and more co-conspirators are caught as the ones still roaming free are still trying to encourage Catiline to continue with the plan, eventually getting noblemen (such as Marcus Crassus, which Sallust claims to have personally known, or at least met) involved which prompted the nullification of several testimonies because it happened to put people in high places in rather uncomfortable scenarios. At the same time, people took the opportunity to get rid of their own political enemies but falsly implicating them in the conjuration. Several attempts to get Julius Caesar in this manner were made, yet Cicero didn't yield.